Ukraine Cyber Chief Illia Vitiuk on Hacktivism and Ransomware

Cybercriminals turned Ukrainian patriots,

the pro-Kremlin hacktivism phenomenon,

and the Clop ransomware group.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with Illia Vitiuk, Chief of Cyber and Information Security at the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), at the Billington Cyber Summit 2023. Vitiuk participated in a fireside chat titled “Ukraine Lessons Learned: Protecting Critical Cyber Infrastructure,” hosted by Microsoft’s Federal Security Chief Technology Officer (CTO), Steve Faehl.

The SBU is the main law enforcement and intelligence agency in Ukraine, playing a crucial role in safeguarding Ukraine’s national security by conducting counterintelligence activities, countering terrorism, combating organized crime, in addition to defending and fighting in cyberspace. The SBU was formed in 1991, shortly after Ukraine gained its independence from the Soviet Union. It succeeded the KGB of the Ukrainian SSR, which was the Soviet Union’s security and intelligence agency in Soviet Ukraine.

Vitiuk was appointed to lead the cyber division of the SBU in November 2021, just a few months before Russia’s invasion of his country.

Since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there has been a significant increase in cyberattacks targeting the country. According to the State Special Communications Service of Ukraine, these attacks have not only tripled in frequency, but have also evolved beyond typical digital intrusions. In some instances, these attacks have been carried out in conjunction with missile strikes, effectively combining kinetic and cyber warfare tactics. Russian offensive cyber campaigns coinciding with sustained bombing have led to serious consequences like blackouts and disruptions to Ukrainian energy facilities. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has characterized these incidents as “energy terrorism.”

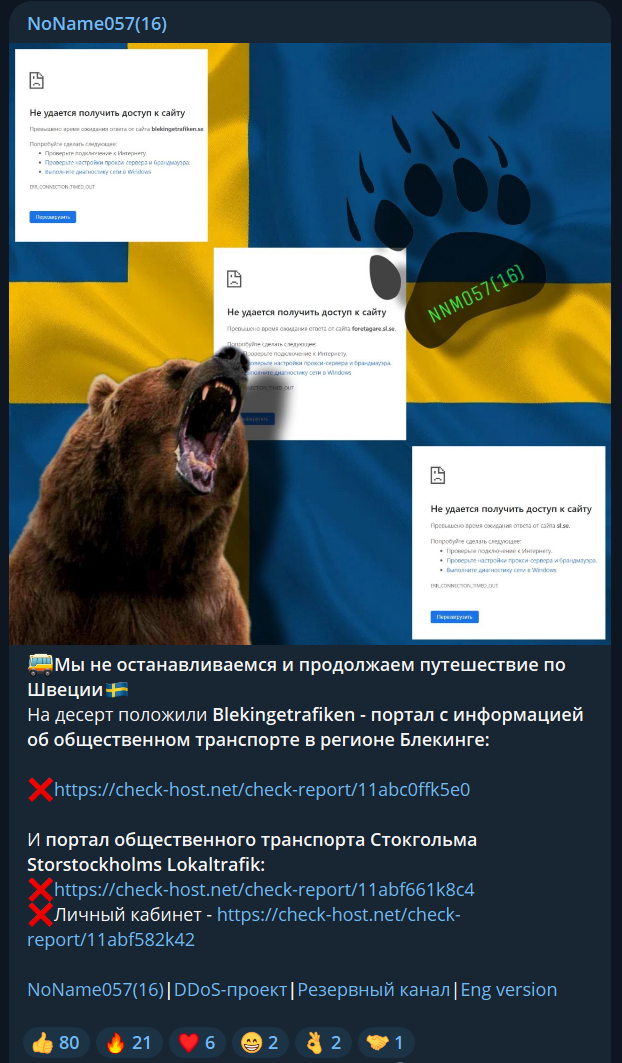

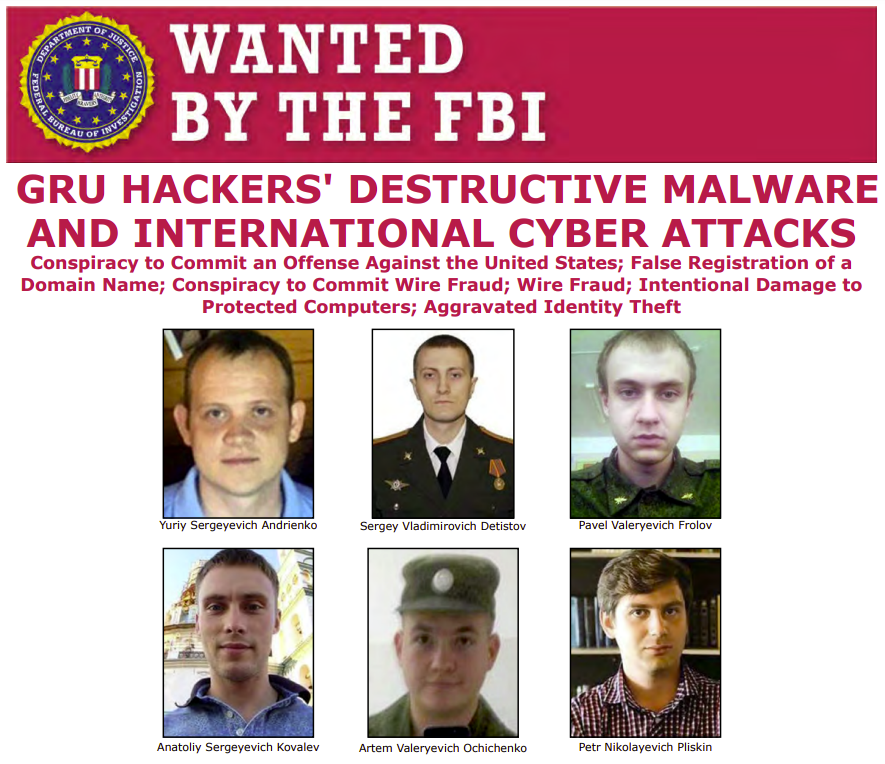

Russian hackers take on various forms, including advanced persistent threat (APT) groups associated with the GRU (Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency), financially motivated ransomware groups, and smaller-scale hacktivists who support the Kremlin and Russian President Vladimir Putin. While extensive reporting has focused on nation-state threat actors, government officials typically do not discuss smaller-scale hacktivism which encompasses activities like website defacement, data leaks, and distributed denial-of-dervice (DDoS) attacks.

I asked Vitiuk for the SBU’s take on modern day pro-Kremlin hacktivism, and he replied: “There is no Russian hacktivism. Maybe it’s a small, small percentage. But in fact, all of these groups like Killnet, Anonymous Sudan, and Cyber Army of Russia – we believe that these are all groups created or orchestrated by the GRU. And we have evidence of that.”

In July 2023, I published an exclusive interview alongside BBC reporter Joe Tidy with Anonymous Sudan, which Vitiuk says is a group created or orchestrated by the GRU. After weeks of continued conversations with the DDoS hacktivists, information gained by Joe Tidy and I suggests that Anonymous Sudan may be just a small group of Sudanese criminal hackers, rather than a Kremlin-run cyber group.

I reached out to Anonymous Sudan’s representative ‘Crush’ for comment, and he replied: “There’s no evidence, even the size of an ant. If there is really any evidence, show me your proof and I’m ready to end Anonymous Sudan, stop the DDoS attacks, close the Telegram channel, and give everything up. Also, I will do a video call with Illia Vitiuk and show him and everybody else my real face – only if he can prove that we are funded by the GRU or that there is any connection to the Russian government at all.”

Vitiuk continued: “Indeed, they can conduct DDoS attacks by themselves. It’s not that difficult to do. But if you see their Telegram channels, you see that there are low profile attacks, or they expose data about our military – and then something interesting happens (referring to cyberattacks preceding military strikes). I believe the GRU legalizes these cyber operations via their controlled Telegram channels and groups.”

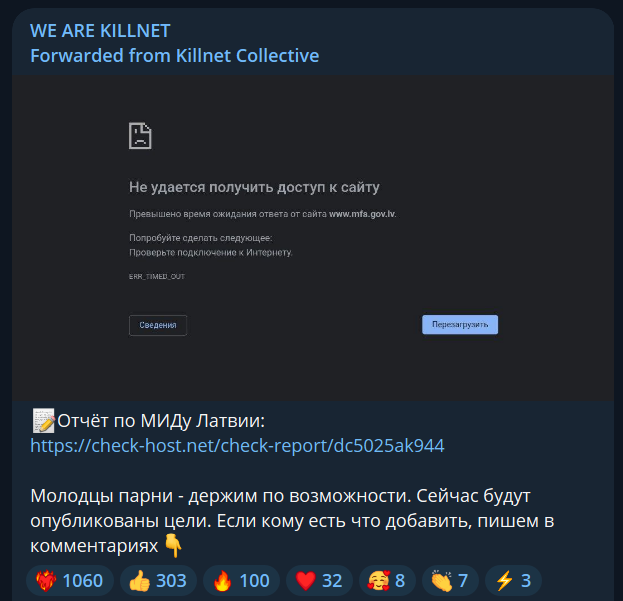

Giving an example of organized hacktivism, Vitiuk said: “Killnet doesn’t usually target Ukraine, but countries supporting Ukraine. There was, for instance, an attempt when they (pro-Kremlin hacktivist groups) all acted together attacking Latvia and their resources, especially the Ministry of Internal Affairs.” The Latvian government has designated Killnet as a terrorist organization following their cyberattacks against Latvian parliamentary web services.

We briefly shifted gears and discussed the current ransomware landscape in Ukraine. Vitiuk explained: “What we see now is that most ransomware groups active prior to the invasion are not very active against Ukraine today. Most of these groups combined people from Russia and Ukraine – you know, somebody is a good coder, somebody conducts lateral movement, somebody conducts privilege escalation, they all have different tasks. And after the beginning of the war, many of these groups fell apart due to ideological reasons. They tried to run away from Russia because they understood that they could either be conscripted, or they will have to work for [Russian] special services. They had problems with that.”

According to FinCEN, the US Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “75 percent of ransomware-related incidents reported between July and December 2021 were linked to Russia, its proxies, or persons acting on its behalf.”

Vitiuk continued, on cybercrime politics: “There were a number of operations like the Conti leaks and Trickbot leaks that actually de-anonymized these people; they constantly have a problem working in ransomware because they understand that the FSB (Federal Security Service) is trying to find them and make them work for them. Unfortunately, a lot of ransomware professionals were from Ukraine. But today, many of them came to us and said: Now we are working for our country and are working against Russia. Unlike Russian so-called hacktivists, we don’t need to force them. They just come and ask: What do you need from us?“

While they sometimes cause a stir in the media, hacktivist website defacement and DDoS attacks are typically low impact and do not affect business continuity or government operations at large. I asked Vitiuk whether the SBU even monitors these groups, or if their time in cyberspace is dedicated exclusively to defending from and penetrating sophisticated Russian groups like APT28. He replied: “We don’t give much attention to these groups. We follow them, but speaking about DDoS, for us, I always say it’s like a head cold. We don’t mind it anymore.”

Discussing the SBU’s priorities, Vitiuk said that his agency was focused on the “very dangerous” operations that the SBU conducts. He went on to describe the SBU’s “recent cyber defensive operations” after attempts by Russian APT Sandworm to attack Ukrainian military situational awareness systems: “They created malware specifically for these systems; we found at least seven malware samples. They tried to penetrate Kropyva.” Kropyva is a proprietary intelligence mapping and artillery software used by hundreds of units across Ukraine. The tool was developed by the nonprofit Army SOS and runs on Android tablets.

Vitiuk continued: “They tried to penetrate Android devices – tablets and phones – that our military uses. And via this system, because one of the ports was open, they could penetrate it and they could even get access to everything that was on the phone, like Telegram and Signal. There was one specific malware, that if the device was connected to Starlink, they could get configurations and understand locations (of users). If you see a lot of tablets and phones connected to Starlink, then you can hit the location with a missile or artillery. So, indeed, very sophisticated operations.”

In 2022, the Center for European Policy Analysis published a report detailing Russian cyberwarfare, which discussed how the Russian Ministry of Education and Science introduced a standard in 2009 that institutionalized “information security” as an area of study in Russian universities. Additionally, the report explained that Russian military intelligence Unit 26165 (aka APT28) has recruited new talent from Russian schools since at least 2014 in cooperation with the FSB’s Institute of Cryptography, Telecommunications, and Computer Science.

Touching on this phenomenon and comparing it with hacktivism, Vitiuk said: “They (Russians) are now teaching students how to implement these disciplines – offensive disciplines – because they understand that they need to scale these operations. They have these laboratories, they have these research institutes, and are constantly developing new malware. So with these hacktivists, you just cannot compare what they are doing, like DDoS, with what true professionals are doing. That’s why as a special counterintelligence service, we are focusing our attention on these [Russian APTs].”

Later in our conversation, Vitiuk stated: “Sometimes people don’t understand that people within IT or cybersecurity are not hackers. It takes a lot of time and a lot of resources to make them actually attack, even for somebody like a ransomware guy. It’s totally different. A guy that puts ransomware somewhere in order to get money – it takes time to teach him how to attack (in a war setting). They take students to the GRU, to the SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service), to the FSB, they have research and development there. So, of course they will evolve, there’s no doubt about it. But we are on the cutting edge, we see all the TTPs (tactics, techniques, and procedures) and we try to work in advance.”

Responding to a question posed by another journalist on the SBU’s offensive operations against Russian APTs, Vitiuk said: “Before the full-scale invasion back in 2022, all we did was protect and defend ourselves. But the time for impunity has gone and we are now conducting counter-offensive [operations] and defending forward. This is a US Cyber Command term: defending forward.” In 2018, the US Department of Defense introduced a new strategic concept called “defend forward.” This approach emphasizes proactive measures meant to disrupt or halt malicious cyber activity at its source, instead of relying on reactive measures and responding to malicious behavior after the fact. US Cyber Command confirmed in 2022 that it had conducted a “full spectrum” of offensive and defensive cyber operations in support of Ukraine in the first year of the war.

Vitiuk cited the need for “important intelligence” when explaining why the SBU conducts offensive operations, adding: “We need to penetrate these APT groups. We need to disrupt their infrastructure in order to understand where they sit in Ukraine now. What are their targets? What are they about to hit? To clean them out of our systems, where are they? So in order to get intelligence: sometimes disruptive and sometimes destructive operations. But I won’t speak about this publicly. A lot of things are happening in Russia.”

Before we ended our conversation, I had to ask the man responsible for cybersecurity in Ukraine about Clop, the notorious ransomware group responsible for targeting over 3,000 US-based organizations and 8,000 global organizations.

In 2021, Ukrainian police announced that they had arrested some Clop affiliates in cooperation with Interpol, US, and South Korean authorities. In the video below, Ukrainian police are shown conducting raids in the Kyiv region on the homes of six individuals linked to the “cash-out/money laundering side of Clop’s business.” They are seen confiscating electronic devices, luxury cars, and nearly $200,000 in cash.

Just one week after the arrest of the operators, Clop published a new dump with confidential data from yet another victim organization. Clearly, the arrests did not have a major impact on the cybercrime gang. More recently, the group made headlines after a summer 2023 hacking spree that followed an SQL injection in the file transfer software MOVEit. According to Emsisoft, as of September 26, 2023, data from state breach notifications, SEC filings, other public disclosures, and Clop’s website indicates that 2,120 victims and 62,054,613 individuals were impacted by MOVEit-related breaches.

Intel 471, a cyber threat intelligence firm, has previously stated that they believe core members of Clop are “probably living in Russia,” and therefore were not subject to any arrests in Ukraine’s 2021 raid.

I asked Vitiuk: “You raided some Clop members two years ago, but they still publish new leaks. We all saw the video of your raid, but they’re still active like crazy. What’s the situation there?”

Vitiuk replied: “Let’s say… I don’t know how to answer it, but I, just – there are some things I won’t disclose publicly. But I am sure that after some period of time, you will know about it.”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.